The painting “Desembarco de los Puritanos en America,” or “The Arrival of the Pilgrims in America,” by Antonio Gisbert shows Puritans landing in America in 1620. By Antonio Gisbert (1834-1902) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Summary

The first winter took many of the English at Plymouth. By fall 1621, only 53 remained of the 132 who had arrived on the Mayflower. But those who had survived brought in a harvest. And so, in keeping with tradition, the governor called the living 53 together for a three-day harvest feast, joined by more than 90 locals from the Wampanoag tribe. The meal was a moment to recognize the English plantation’s small step toward stability and, hopefully, profit. This was no small thing. A first, deadly year was common. Getting through it was an accomplishment. England’s successful colony of Virginia had had a massive death toll — of the 8,000 arrivals between 1607 and 1625, only 15 percent lived.

But still the English came to North America and still government and business leaders supported them. This was not without reason. In the 17th century, Europe was in upheaval and England’s place in it unsure. Moreover, England was going through a period of internal instability that would culminate in the unthinkable — civil war in 1642 and regicide in 1649. England’s colonies were born from this situation, and the colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and the little-known colony of Providence Island in the Caribbean were part of a broader Puritan geopolitical strategy to solve England’s problems.

Analysis

Throughout the first half of the 17th century, England was wracked by internal divisions that would lead to civil war in 1642. Religion was a huge part of this. The dispute was over the direction of the Church of England. Some factions favored “high” church practices that involved elaborate ritual. The Puritans, by contrast, wanted to clear the national religion of what they considered Catholic traces. This religious crisis compounded a political crisis at the highest levels of government, pitting Parliament against the monarchy.

By the beginning of the 17th century, England had undergone centralizing reforms that gave the king and his Parliament unrestricted power to make laws. Balance was needed. The king had the power to call Parliament into session and dismiss it. Parliament had the power to grant him vital funds needed for war or to pay down debt. However, Parliament had powerful Puritan factions that sought not only to advance their sectarian cause but also to advance the power of Parliament beyond its constraints. Kings James I and his son Charles I, for their part, sought to gain an unrestrained hold on power that would enable them to make decisive strategic choices abroad. They relied, internally and externally, on Catholics, crypto-Catholics and high church advocates — exacerbating the displeasure of Parliament.

Both kings continually fought with Parliament over funding for the monarchy’s debt and for new ventures. Both dissolved Parliament several times; Charles ultimately did so for a full 11 years beginning in 1629.

Europe in 1600

Spain was England’s major strategic problem on the Continent. Protestant England saw itself as under constant threat from the Catholic powers in Europe. This led to problems when the people came to see their leaders, James I and his son Charles, as insufficiently hostile to Spain and insufficiently committed to the Protestant cause on the Continent. In order to stop mounting debt, shortly after taking power James made the unpopular move of ending a war with Spain that England had been waging alongside the Netherlands since 1585. In 1618, the Thirty Years’ War broke out in the German states — a war that, in part, pitted Protestants against Catholics and spread throughout Central Europe. James did not wish to become involved in the war. In 1620, the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II, a relative of Spain’s King Philip III, pushed Frederick V, the Protestant son-in-law of England’s King James, out of his lands in Bohemia, and Spain attacked Frederick in his other lands in the Rhineland. The English monarchy called for a defense of Frederick but was unwilling to commit to significant military action to aid him.

Puritan factions in Parliament, however, wanted England to strike at Spain directly by attacking Spanish shipments from the Americas, which could have paid for itself in captured goods. To make matters worse, from 1614 to 1623, James I pursued an unpopular plan to marry his son Charles to the Catholic daughter of Philip III of Spain — a plan called the “Spanish Match.” Instead, Charles I ended up marrying the Catholic daughter of the king of France in 1625. This contributed to the impression that James and Charles were too friendly with Spain and Catholicism, or even were secret Catholics. Many Puritans and other zealous promoters of the Protestant cause began to feel that they had to look outside of the English government to further their cause.

Amid this complex constellation of Continental powers and England’s own internal incoherence, a group of Puritan leaders in Parliament, who would later play a pivotal role in the English Civil War, focused on the geopolitical factors that were troubling England. Issues of finance and Spanish power were at the core. A group of them struck on the idea of establishing a set of Puritan colonial ventures in the Americas that would simultaneously serve to unseat Spain from her colonial empire and enrich England, tipping the geopolitical balance. In this they were continuing Elizabeth I’s strategy of 1585, when she started a privateer war in the Atlantic and Caribbean to capture Spanish treasure ships bound from the Americas. Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were part of this early vision, but they were both far too remote to challenge the Spanish, and the group believed that the area’s climate precluded it from being a source of vast wealth from cash crops. New England, however, was safe from Spanish aggression and could serve as a suitable starting point for a colonial push into the heart of Spanish territory.

The Effects of Spanish Colonization

Spain’s 1492 voyage to the Americas and subsequent colonization had changed Europe indelibly by the 17th century. It had complicated each nation’s efforts to achieve a favorable balance of power. As the vanguard of settlement in the New World, Spain and Portugal were the clear winners. From their mines, especially the Spanish silver mine in Potosi, American precious metals began to flow into their government coffers in significant amounts beginning in 1520, with a major uptick after 1550. Traditionally a resource-poor and fragmented nation, Spain now had a reliable revenue source to pursue its global ambitions.

Spanish Colonies in the Carribbean

This new economic power added to Spain’s already advantageous position. At a time when England, France and the Netherlands were internally divided between opposing sectarian groups, Spain was solidly Catholic. As a result of its unity, Spain’s elites generally pursued a more coherent foreign policy. Moreover, Spain had ties across the Continent. Charles V was both king of Spain and Holy Roman emperor, making him the most powerful man of his era. He abdicated in 1556, two years before his death, and divided his territories among his heirs. His son, Philip II of Spain, and Charles’ brother, Ferdinand I, inherited the divided dominions and retained their ties to each other, giving them power throughout the Continent and territory surrounding France.

Despite having no successful colonies until the beginning of the 17th century, England did see some major benefits from the discovery of the Americas. The addition of the Western Atlantic to Europe’s map and the influx of trade goods from that direction fundamentally altered trade routes in Europe, shifting them from their previous intense focus on the Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean to encompass an ocean on which England held a unique strategic position. The nearby Netherlands — recently free from Spain — enjoyed a similar position and, along with England, took a major new role in shipping. By the middle of the 17th century, the Dutch had a merchant fleet as large as all others combined in Europe and were competing for lands in the New World. Sweden, another major European naval power, also held a few possessions in North America and the Caribbean. (This led to curious events such as “New Sweden,” a colony located along the Delaware River, falling under Dutch control in the 1650s and becoming part of the “New Netherlands.”)

England’s Drive Into the New World

In spite of its gains in maritime commerce, England was still far behind Spain and Portugal in the Americas. The Iberian nations had established a strong hold on South America, Central America and the southern portions of North America, including the Caribbean. Much of North America, however, remained relatively untouched. It did not possess the proven mineral wealth of the south but it had a wealth of natural capital — fisheries, timber, furs and expanses of fertile soil.

However, much of the population of the Americas was in a band in central Mexico, meaning that the vast pools of labor available to the Spanish and Portuguese were not present elsewhere in North America. Instead, England and other colonial powers would need to bring their own labor. They were at a demographic advantage in this regard. Since the 16th century, the Continent’s population had exploded. The British Isles and Northwest Europe grew the most, with England expanding from 2.6 million in 1500 to around 5.6 million by 1650. By contrast, the eastern woodlands of North America in 1600 had around 200,000 inhabitants — the population of London. Recent catastrophic epidemics brought by seasonal European fishermen and traders further decimated the population, especially that of New England. The disaster directly benefited Plymouth, which was built on the site of the deserted town of Patuxet and used native cleared and cultivated land.

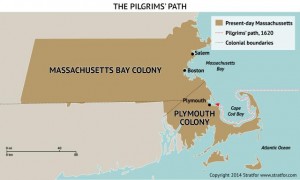

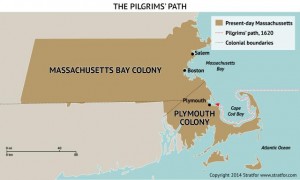

After its founding in 1620, Plymouth was alone in New England for a decade and struggled to become profitable. It was the first foothold, however, for a great Puritan push into the region. In time, this push would subsume the tiny separatist colony within the larger sphere of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This new colony’s numbers were much higher: The first wave in 1630 brought 700 English settlers to Salem, and by 1640 there were 11,000 living in the region.

Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were different from nearby Virginia. Virginia was initially solely a business venture, and its colonists provided the manpower. New England, by contrast, was a settler society of families from the start. Both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were started by English Puritans — Christian sectarians critical of the state-run Church of England. Plymouth’s settlers were Puritan separatists who wanted no connection to England. Massachusetts Bay’s colonists were non-separatist Puritans who believed in reforming the church. For both, creating polities in North America furthered their sectarian political goals. The pilgrims wanted to establish a separate godly society to escape persecution; the Puritans of Salem wanted to establish a beacon that would serve to change England by example. Less known, however, is that the financial backers of the New England colonies had a more ambitious goal of which New England was only the initial phase.

In this plan, Massachusetts was to provide profit to its investors, but it was also to serve as a way station from which they could then send settlers to a small colony they simultaneously founded on Providence Island off the Miskito Coast of modern Nicaragua. This island, now part of Colombia, was in the heart of the Spanish Caribbean and was meant to alter the geopolitics of Central America and bring it under English control. It was in this way that they hoped to solve England’s geostrategic problems on the Continent and advance their own political agenda.

Providence was an uninhabited island in an area where the Spanish had not established deep roots. The island was a natural fortress, with a coral reef that made approach difficult and high, craggy rocks that helped in defense. It also had sheltered harbors and pockets of fertile land that could be used for production of food and cash crops.

It would serve, in their mind, as the perfect first foothold for England in the lucrative tropical regions of the Americas, from which it could trade with nearby native polities. In the short run, Providence was a base of operations, but in the long run it was to be a launchpad for an ambitious project to unseat Spain in the Americas and take Central America for England. In keeping with Puritan ideals, Providence was to be the same sort of “godly” society as Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth, just a more profitable one. Providence Island would enable the English to harry Spanish ships, bring in profit to end disputes with the crown and bolster the Protestant position in the Thirty Years’ War.

But while Massachusetts Bay would succeed, Providence would fail utterly. Both Massachusetts Bay and Providence Island received their first shipment of Puritan settlers in 1630. Providence was expected to yield immense profits, while Massachusetts was expected to be a tougher venture. Both were difficult, but Providence’s constraints proved fatal. The island did not establish a cash crop economy and its attempts to trade with native groups on the mainland were not fruitful.

The island’s geopolitical position in Spanish military territory meant that it needed to obsessively focus on security. This proved its downfall. After numerous attacks and several successful raids on Spanish trade on the coast, the investors decided in 1641 to initiate plans to move colonists down from Massachusetts Bay to Providence. Spanish forces received intelligence of this plan and took the island with a massive force, ending England’s control.

Puritan Legacies

The 1641 invasion ended English settlement on the island, which subsequently became a Spanish military depot. The Puritans left little legacy there. New England, however, flourished. It became, in time, the nearest replica of English political life outside of the British Isles and a key regional component of the Thirteen Colonies and, later, the United States. It was the center of an agricultural order based on individual farmers and families and later of the United States’ early manufacturing power. England sorted out its internal turmoil not by altering its geopolitical position externally — a project that faced serious resource and geographical constraints — but through massive internal upheaval during the English Civil War.

The celebration of the fruits of the Plymouth Colony’s brutal first year is the byproduct of England’s struggle against Spain on the Continent and in the New World. Thus, the most celebrated meal in America comes with a side of geopolitics.

________________________________________________________________

Reprinting or republication of this report on websites is authorized by prominently displaying the following sentence, including the hyperlink to Stratfor, at the beginning or end of the report.

“Thanksgiving and Puritan Geopolitics in the Americas is republished with permission of Stratfor.”

Read more: Thanksgiving and Puritan Geopolitics in the Americas | Stratfor

Follow us: @stratfor on Twitter | Stratfor on Facebook

http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/thanksgiving-and-puritan-geopolitics-americas#axzz3K0JIYeVP